For the first time in its history, a large manufacturing company set up a steering committee for the learning and development (L&D) function. This was a breakthrough.

The company's top leadership finally recognized that its success depended on developing its workforce.

An executive vice president sat on the committee, representing a number of key business units. When he learned that the L&D budget was allocated evenly across the product lines, he protested. "Just two of these products generate 80% of our profit. Why aren't we investing heavily in those two?"

The EVP's comment completely changed the focus of the L&D function. The committee's discussion now reflected its mandate to set priorities. What would they spend their money on? What would give them the highest-value return? Instead of the Chief Learning Officer (CLO) making decisions in isolation, there was now a team in place whose members were prepared to assess the company's training needs and direct resources accordingly.

In the following year, skill levels measurably increased, and so did profits. The new governance model, with a committee allocating funds, positioned L&D as a true enabler of the business.

A governance structure in L&D is a move from implicit to explicit practices. It brings rigor and structure to decision-making practices that would otherwise be nebulous and ill-defined. It is a recognition that L&D is, fundamentally, a strategic function - equally critical for the organization's growth and for its survival in turbulent times.

As L&D professionals, we need strong governance structures to keep pace with the accelerating speed of change. Many of us have spent our careers delivering workshops and programs. Now we are expected to respond to the impact of shifting technologies, geopolitical events, and new economic realities, all of which require rapid reskilling at scale.

"The pace of change has never been this fast," said Justin Trudeau at Davos in 2018, referring to world events, "and it will never be this slow again." That turned out to be an understatement. Since then, humanity has gone through some of the biggest changes in its history - a global pandemic, the rise of artificial intelligence, and massive geopolitical change, all in just a few years.

The new pace of change directly affects the L&D function, at the most granular level. In the past, for instance, a company's sales curriculum might stay the same for 4 or 5 years. Now, it is continuously revised as the product mix evolves, new technology comes on board, and supply chains shift. When confronted with changes in leadership, strategy, processes, and priorities, CLOs must be able to respond swiftly and decisively.

Approaches to L&D governance will vary from one company to another. However, four elements are always critical: a common oversight structure and process for decision-making; a shared set of L&D design principles that apply throughout the organization; a means for connecting L&D leaders and their key constituents throughout the organization; and mechanisms for continuous improvement.

1. Oversight and decision-making

Any comprehensive L&D function must make enterprise-wide decisions. It must ensure the learning and development initiatives align with organizational goals and standards.

Rather than "taking orders" from separate stakeholders within the company, it must be strategic: Determining the right target audiences for each learning solution and making sure those audiences are reached.

In the L&D system, oversight and structure determine decision rights and accountability. Who is responsible for setting standards for the whole L&D function and making sure they meet the criteria? Who is responsible for each offering, ensuring that it is aligned with the company's strategic purpose? Each domain within the company may have its own answer, depending on what type of decisions are needed. Several models are emerging:

A company-wide steering committee, overseeing all L&D activity. In companies where L&D is recognized for its strategic value, this committee may sit one level below the executive team. Generally, the business leaders for prominent products

and services are represented. Since it covers a range of business, the committee must take the company's overall needs into account, and not just one or two products.

At a large biopharmaceutical company, this type of L&D governance structure was put in place when the global CLO brought together the heads of learning for each of the business units and functions. They had minimal guidance or structure beyond a set of company-wide people imperatives, one of which was: "Create a culture of lifelong learning." The global CLO, who chaired the new Learning Council, took care not to impose any purpose or direction. Instead, at their first meeting, the members "stormed and formed" to identify a vision for their collective efforts. It was clear that all would have a say in what their teams could do together, and that the Council, not any individual, would set the policies. This created early engagement and buy-in. It enabled the team to achieve some early enterprise-wide wins together, such as launching a new learning experience platform and a single approach to skill development for people leaders.

Matrix structures for accountability and direction. An L&D decision-making committee might be placed within the HR function, synchronizing L&D more closely with recruiting and promotion priorities. There could also be "dotted line" approval links to business units and relevant functions. These structures can integrate L&D more closely with the rest of the organization, but they also carry the risk of bureaucracy. Those links can become approval requirements that slow down decisions.

In one such committee, where the first session was locked in debate, two members took charge. The CLO and the executive who represented product lines demanded and received decision rights. They also took on the responsibility of managing discussion: ensuring that all voices were heard. The CLO came to the table with a prepared storyline: "We've confirmed several skill-building needs this quarter, and we've proposed some new programs to meet them." If the other leaders on the committee agreed, the CLO could then lean on them to support those offerings and go back to the L&D organization with a clear overall direction.

The CLO and L&D function as the central source of authority. In these cases, the organization's support for the CLO - in terms of approval, budget, and information - should be clear. Advisors and stakeholders throughout the company should be available, to ensure that the L&D function is aware of the priorities.

One large, multinational financial services organization set up its governance

system this way. The CLO remained the source of authority, but he asked every L&D leader with an idea to present it to a representative panel of senior leaders from around the company. About half of the originator proposals make it through the first round. They are asked to make revisions based on panel feedback and come back to the panel for final approval. This rigorous process benefits both the content originators and the content recipients.

Whatever the governance structure may be, its primary means of establishing authority is the budget. A large company may devote $50-500 million per year to L&D. The governance structure should allocate that money according to business priorities. The rationale should be visible: it should showcase how L&D initiatives are seamlessly integrated into the organization's strategic objectives, actively driving tangible business results, and responding flexibly as the world changes around it.

2. L&D design principles

Governance also involves a system of explicit principles for the L&D function. These are guidelines for designing learning experiences, providing consistency in the quality and content, and applicable to different parts of the world or service offerings. Design standards ensure that all content is of high quality, meets established requirements, comes from reputable vendors, and is consistent across the organization By codifying and articulating these principles, the L&D function also establishes a common checkpoint that everyone can discuss and ultimately with which the entire company can align.

The principles will typically reflect the interests of many stakeholders in a company: administrators, instructors, learners, and other employees. They cover the strategic learning objectives, monitoring the progress towards achieving these objectives, and ensuring that learning resources are used responsibly and effectively.

Specific principles might include:

Guardrails for maintaining quality: Good governance sets and maintains high standards for learning experience design, delivery, and assessment - -contributing to the overall quality and effectiveness of the learning initiatives.

Mechanisms for mitigating risk: Training must cover compliance, legal issues, and ethical concerns, and governance must ensure adherence to policies and regulations to minimize reputational risks and legal liabilities.

Content: Principles can articulate criteria for topics and emphasis. This must align with the organizational goals and standards.

Transparency and Simplicity: Principles can clarify how decisions are made and

how resources are allocated. This builds trust, engagement, and buy-in among

stakeholders and constituents in the company. Principles can also help L&D "keep it simple," by stating the priorities and methods in plain language in an accessible central place.

Empowerment and Engagement: The principles cover the overall learning

environment: an inclusive system, a catalyst for individual and collective growth,

and a source of psychological safety and employee engagement.

Collaboration and Partnership: Principles can explicitly promote collaboration

across business units and with selected outside organizations like universities, thus aligning L&D with broader talent strategies for maximum impact.

Measurable Impact: Principles should establish metrics and KPIs that will be used to assess the impact of L&D initiatives, providing insights for continuous improvement and demonstrating the value of L&D to the organization.

3. Relationships with constituent groups

The knowledge in most organizations is not confined to top leadership. Managers at every level have ideas about their talent needs going forward. Their insights and observations are critically important, and they may represent constituents throughout the organization.

A network of established relationships is thus a critical aspect of L&D governance. It's tempting to frame this network as the global executives with budgetary and staff approval. However, learning is not always top of mind for them; it's one of many aspects of the business they must consider. This network is composed of a broader base of constituents: the people in every organization who understand the relationship between skills and success. They need to be more formally brought into the L&D orbit.

Typically, there are four types of constituents:

Sponsors of L&D initiatives are typically the local and line executives who are committed to the growth and development of the workforce in their domains. Having their sponsorship is a table stake for L&D. Without it, the function lacks the necessary support to thrive. The network must explicitly include them.

Champions of learning are eager, visible participants in the skills development process. They may be line leaders, technical specialists, or enthusiastic members of teams in fast-growing fields. They are typically in a good position to influence others, and some may end up becoming teachers, mentors, or coaches themselves.

HR business partners and Talent Centers of Excellence can help drive the

integration of learning initiatives with broader talent management strategies. These could include succession planning, performance management, and employee engagement. Stronger integration with people-related functions ensures that L&D efforts contribute directly to building a competent and competitive workforce.

Independent L&D groups include the ad hoc "enablement" and business-embedded L&D teams that crop up within many companies, often within local business units or HR functions. They serve as the leaders for the development of technical or specialized skills unique to their part of the business. Though these groups fall out of the centralized L&D ecosystem, they play an important role.

Challenges arise when they are not aligned with the center. It is in the CLO's best interest to include them within some kind of formal governance structure, even if it's as simple as recognizing them and inviting them to participate in joint activities.

In one global financial services company, the central L&D function was complemented by myriad local and business-specific learning initiatives. This business-embedded learning ecosystem was not organized or recognized, but the people dedicated to it outnumbered the global L&D team. Its extent was only discovered after a company-wide audit of learning management system (LMS) procurement. Instead of seeking to shut down or absorb these activities, the CLO invited them to voluntarily join a global Community of Practice. This became a robust ongoing group of enthusiastic participants, with a formal Learning Council comprising leaders of technical and local training initiatives. The central L&D team gained access to an expanded army of learning professionals and ambassadors to support global initiatives, pilot new programs, assist with development and early feedback, and help with communication and engagement efforts.

Explicit recognition of constituent groups has many advantages. It enables scalability through coordinated efforts. It also brings more diverse perspectives into the L&D orbit, reduces program duplication, fosters collaboration, and helps CLOs keep up with the organization's needs. All offerings can now be aligned with a core skill-building curriculum, which amplifies the impact of the learner's experience, even if they only attend one part.

These relationships are also early detection "tentacles," bringing in feedback that might not be otherwise available to a CLO. Constituents see new demand for skills before it surfaces elsewhere. They are often among the first to hear when a training session has problems. They tend to know about inadequate follow-through, such as when people are trained in new skills but not placed in any projects that use them.

4. Mechanisms for Continuous Improvement

With the appropriate feedback mechanisms and leadership efforts, the L&D function can continue to raise the value of its offerings. Evaluation, conversation and reflection practices thus become an important aspect of governance structures, even if they are often unseen. They are not just ways of improving learning solutions, but of improving the governance process itself.

After a program is launched, iterative decision processes can allow for continuous learning and improvement. There should be ongoing just-in-time adjustments based on continuous feedback and evolving circumstances. When the L&D function is oriented to continuous improvement, Individuals grow accustomed to ongoing, habitual raising of their skills. Feedback loops are built into the L&D governance process. Change is expected and embraced.

This resilience can help CLOs keep the governance structure stable when there is a shift in top organizational leadership or direction. This so-called "swinging pendulum of transformation and transition" can take place without disrupting L&D, because the practice of continuous improvement makes it easier to pivot.

One way to instill regular feedback loops is to institute regular "after-action reviews" for significant learning endeavors if they don't already exist. These are opportunities for teams of L&D leaders to look back at the feedback and results of each offering and discuss how they might be improved. What went wrong, and why? What went well, and why? How did we demonstrate alignment with business priorities? What evidence exists that people are putting it to use?

CLOs and other learning leaders can also open informal discussions- with stakeholders and within the L&D group- - about the ongoing impact of skill-building efforts. These can become gathering points to talk about the outcomes from specific programs, especially if data is available on how the training influenced decisions. From there, it's possible to talk about the mindset and practices of the L&D teams.

As they face disruption and rapid change, learning professionals must make decisions rapidly, mobilize people, set up designs, and frequently revise offerings based on feedback. This requires a frame of mind oriented toward speed and results. The mindset of the learning leader is itself an aspect of governance. Reflection and individual practice are forms of continuous improvement. They can be thought of as internal governance: adopting a mindset of continuous improvement and fostering a culture of innovation.

Managing Resistance to L&D Governance

CLO Council members identified resistance within the organization as one key challenge in standing up learning governance. This type of resistance can significantly impact a CLO's ability to establish and execute their L&D strategy - making it very difficult to deliver on the promise of being a strategic driver of organizational success.

Overcoming resistance is thus critical in driving the adoption of and engagement in governance processes. Surfacing the reasons behind the resistance provides the CLOs with the information they need to tailor their approach when working to bring others on board. Addressing the resistance is a foundational step to CLOs' and L&D's ability to operate effectively and efficiently, to adapt quickly when necessary, and to deliver on the promise of being a strategic driver of organizational success.

In most companies, there may be several reasons for resistance:

Business leaders may resist learning governance based on a perception that

learning is merely an employee benefit, a check-the-box activity, rather than a strategic driver of business outcomes. It is imperative that L&D clearly articulate the benefits of engagement and emphasize the strategic impact investments.

HR and Talent CoE leaders may also exhibit resistance. With their own priorities and initiatives to focus on, they may perceive learning governance as an additional layer of complexity that distracts from their core responsibilities. Silos across HR and Talent functions can further exacerbate the resistance, as each team operates independently and fails to recognize the importance of their roles. Overcoming these barriers requires recognizing the need for collaboration among HR and Talent functions and ensuring a holistic approach to learning and development.

L&D teams may feel apprehensive about relinquishing control over learning initiatives or adjusting to new processes and structures. If they don't recognize the value proposition of learning governance, they may perceive it as a bureaucratic hurdle rather than a strategic enabler. Overcoming this resistance requires clear communication, involvement of L&D teams in the design and implementation of governance frameworks, and a focus on demonstrating the benefits of standardized processes for learning outcomes and organizational performance.

The best approach to overcoming resistance to learning governance starts with proactively shaping and communicating the narrative around the value and benefits of governance - in language that resonates with the target audience. Clearly articulating the value and benefits through the lens of the different stakeholders and constituents helps CLOs gain credibility and are more likely to secure their buy-in and engagement.

The benefits include all the elements described throughout this article.

For example: Strategic alignment with the organization's goals will drive tangible results. Better governance will make L&D more flexible and encourage a culture of innovation. It creates an environment where people embrace learning as a catalyst for their own growth. Governance promotes collaboration across business units, leading to more effective programs at lower costs. Finally, it establishes metrics and KPIs to assess the impact of L&D initiatives and continue to improve them. Proactively shaping the narrative around learning governance can go a long way toward bringing people together around the need for better skills. The narrative can describe an agile L&D function, with continuous collaboration and flexible structures: for example, program approval and cost allocation processes that respond swiftly to emerging challenges, opportunities, and changes in the organizational landscape.

When the narrative recognizes stakeholder concerns and paints a credible picture of how they will be addressed, people are more likely to come on board. When the narrative describes results that lead to actual gains, people may become enthusiastic.

The Right Level of Control

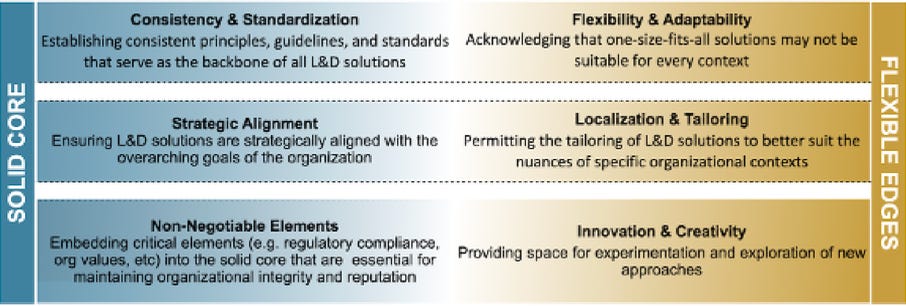

Another pivotal challenge for CLOs involves finding the right balance between too much and too little control. It's essential to create governance structures and processes that recognize the need for a strong and unwavering foundation, while maintaining the flexibility required for the organization's diverse needs and dynamics. CLOs must consider consistency versus flexibility, global alignment versus local tailoring, and core integrity versus innovation (see Exhibit 1:)

Exhibit 1: The balances inherent in an L&D governance system

Stakeholders may perceive a highly controlled L&D function as being a hindrance rather than an enabler of business strategy. Overly restrictive controls can stifle creativity and innovation, especially when rigid rules inhibit the exploration of new approaches and ideas. This can lead to stagnant and outdated learning programs that fail to engage the modern learner.

Excessive controls can also lead to a lack of agility and responsiveness in addressing learning needs, slowing down decision-making and implementation, and impeding the organization's ability to quickly adapt to market changes and capitalize on emerging opportunities. They may be perceived as micromanagement, discouraging engagement and collaboration, and push leaders to direct their teams to work outside of the L&D ecosystem. Additionally, too many controls can increase administrative burden, diverting time and resources away from core learning activities and strategic initiatives.

Too few controls also diminish an L&D function's success. This can lead to misalignment of learning efforts and inconsistency in the quality and effectiveness of learning solutions. Inadequate controls can also lead to wasted time, budget, and resources, as companies keep adding ineffective or unnecessary learning activities. Stakeholder engagement and buy-in may suffer. Moreover, without proper controls, there is a greater risk of non-compliance with regulatory requirements and internal policies, potentially exposing the organization to legal and reputational risks.

A Call to Action

Many companies talk about creating a learning culture. L&D governance is a means for doing this. Arguably, the most important role of the Chief Learning Officer is to orchestrate that governance process.

As the landscape of business and technology continues to evolve at warp speed, CLOs must establish robust governance systems. Every L&D governance system will be different, but each will be the cornerstone of organizational learning in its company.

Governance serves a catalyst for strategic alignment, resource optimization, stakeholder engagement, risk mitigation, and continuous improvement. It positions L&D for sustainable success in the cyclone of change that surrounds us. Let us embrace the call to action, prioritize learning governance, and actively and relentlessly champion its implementation.

About the Authors

We extend our gratitude to all the authors and thought partners for their invaluable contributions to this article. Their combined expertise and insights have been instrumental in shaping the content, providing readers with a comprehensive understanding of the crucial elements for effective L&D Governance.

The Learning Forum + CLO LIFT Leaders

Brian Hackett, Founder and CEO of The Learning Forum

Meighan Hackett Poritz, Co-founder and Managing Director, The Learning Forum

Noah G. Rabinowitz, Chief Learning Officer and CLO LIFT Co-founder