CLO LIFT: The Skills Accelerator

The Learning Forum

Transforming the L&D function to deliver real-world capabilities

Not long ago, a major professional services firm launched a new artificial intelligence consulting practice with a target of reaching $100 million in revenue in multiple years. They asked the Chief Learning Officer (CLO) to build the capacity to train hundreds o professionals per quarter in AI, blockchain, robotics, and other advanced technologies. The new program would have to train both existing staff and new recruits, to scale up or down as needed, and to evolve as skills changed.

Ten years earlier, this program would have used conventional classroom-based courses, each taking months to design. Now, the field is changing too quickly. Moreover, the firm's learning and development (L&D leaders knew that formal learning would not suffice. Their own data, along with outside research, had consistently found that people retain a very small amount of what they hear in lectures and talks. They learn much more from teaching others, and still more from action: working on teams that explicitly use their new skills in real work. People learn the most when they can act, practice, and reflect on what they do.

Thus, the CLO, with top leadership approval, created an entirely new broad-based skills accelerator for advanced technologies. It was set up to integrate with day-to-day work and keep up with the pace of client demand, based on staffing data rather than estimates. (Business leaders sometimes overestimated how many people they would need.) The 3-month program minimized classroom learning, replacing it with self-assessed online exercises, "bootcamp"-style intensives and apprenticeships with the firm's tech experts. The firm used the training results explicitly to assign staff to real-world projects, treating them as opportunities for further learning, and tracking revenue impact.

Overall, the company became more agile and responsive to technology changes. There were bottom-line benefits as well. Moreover, at a time rampant with tech layoffs, staff members felt more confident about keeping their jobs.

The skills accelerator concept represents a reframing of L&D's potential. It can have a significant impact on an organization's capabilities, on an accelerated timeline. The more intensive and well-designed the effort, the more proficient the company becomes. This makes it more capable of generating revenue, allowing more investment of time and resources in successive cycles. This virtuous cycle enables the organization's skills to surge forward at a pace that is equal to or faster than the demands of the business and markets.

A skills accelerator has momentum, but it does not run by itself. Its practices can seem unfamiliar and even counterintuitive to many. Someone, typically the CLO, must design it and keep it moving, integrating that effort with the rest of the organization's processes and its growth.

The pressure for proficiency

There is always a need for workforce upskilling and reskilling. Now, however, that need has intensified. With almost a quarter of jobs in the US expected to change by 2027, and the pace of change increasing, upgrading skills hasbecome a strategic imperative for companies and employees.

The primary cause is the speed and scale of technological change: computing power, bandwidth, artificial intelligence, robotics, sensors, and more. Organizations need to rapidly upskill and reskill individuals for jobs that did not exist just a few years ago- like GenAI auditor or robotics upgrade coordinator - where sufficient skills levels do not widely exist in the talent marketplace. Individuals need to rapidly upskill if they want to acquire new knowledge, skill, and ability to advance to the next opportunity.

Meanwhile, the supply of labor is dwindling and moving to emerging economies. In the industrialized world, populations continue to age, birth rates continue to decline and the overall level of education has plateaued. Organizations are thus competing for a larger share of a constrained talent pool. In the US alone, 20% of Americans are expected to hit retirement age by 2030 vs.16.8% today. Businesses need to reskill the pie rather than expect the skilled population to grow organically. The World Economic Forum estimates that between 1 and 3 billion people will need extensive skill development by 2030.

Employee preferences have also changed. There are increased demands for new working models, such as remote working and flexible hours. Non-traditional work structures - temporary, gig, and part-time jobs - are more prevalent. Workers seek the alignment of work, values, and purpose. They want organizations to provide them with compelling opportunities and environments that they find rewarding, challenging and valuable. This invariably means enabling them to keep learning new skills.

Finally, the tools for learning are undergoing dramatic change. Suppose, for example, that mid-level managers need to learn better protocols for holding staff meetings. They can now turn to GenAl tools, explain their current difficulties, and receive suggestions for interventions on the spot, with unlimited opportunities to test their skills in simulations and return for further guidance. Though it comes from a bot, this kind of skill-building can do more to change behavior over time than a four-hour course on holding difficult conversations.

Many top executives are aware of these issues. They respond by demanding that their L&D departments move faster to develop the skills - in fields like Al, biotech, blockchain and robotics - that are needed right now in the marketplace. If L&D can't develop those capabilities in-house, then the company must recruit them, which can be much more expensive and less effective.

Aaron de Smet, et al, "What is the Future of Work?", McKinsey, January 23, 2023: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey- explainers/what-is-the-future-of-work

The L&D function does not always keep pace with those demands. CLOs may be unduly influenced by the business leaders with the loudest voices or distracted by "flavor-of- the-month" technologies and practices that seem appealing at first glance, but don't live up to their promises. Another distraction can be focusing on long-term strategic enablers: creating a comprehensive skills taxonomy, a lofty plan, or a full-scale internal marketplace. Many organizations need these, but not at the expense of the short-term skills that are critical for today's business priorities. The more urgent L&D challenge is to surge the most-needed skills and learn to move with simplicity and speed.

"Your success in life isn't based on your ability to simply change," says business writer Mark Sanborn. "It is based on your ability to change faster than your competition, customers, and business." This aphorism applies to the company, the individuals working there, and the L&D function itself. Resources are limited and the need is urgent; CLOs must focus attention on the few highest priority demands and raise their game in those areas.

CLOs must ask: Is our work building lasting, relevant skills right now? Are we delivering business impact? Is the work building or diminishing L&Ds effectiveness and credibility? If the answers to any of these questions is no, then perhaps it is time for a skills accelerator approach. Though the details may vary from one organization to the next, there are always three basic considerations:

• Pace: Move from reactive to proactive offerings, recognizing the increasing importance of speed in delivery;

• Relevance: Move from marginal to mission-critical skills, enabling the skills accelerator to drive immediate business impact;

• Scope: Move from silos to scope, breaking down the traditional organizational boundaries to cultivate skill utilization across the entire enterprise.

Pace

The need for speed is fundamentally changing the L&D paradigm. Just a few years ago, recruiters for the function placed a high value on traditional instructional design skills. Today, an L&D candidate needs strong analytics capabilities and, ideally some GenAl experience. The days of taking 12 months to design and develop a learning curriculum are long gone. Those who don't speed up will be viewed as a cost center and shunted to the side.

Budgeting for L&D organizations, which is typically decided annually, can no longer keep up. Nor can the existing skill-based infrastructure: the digital platforms, courseware, and organizational structures. All of this must be changed instantly, with the agility usually associated with software launches.

Some speed will come from using tools like Generative A.l. The L&D function is now capable of building precision training and guidance systems at an unprecedented speed. This will allow customized training that will help people upskill and reskill more successfully. It must be carefully managed (for example, for misinformation and deepfakes, as well as the protection of copyrighted material), but the speed of creation is nonetheless much faster.

Simulations are also much easier to build at speed. A"virtual twin," which allows people to test their decisions in advance, formerly took weeks to design and develop. Now a GenAl system can create one in a few hours with a succession of prompts. Similar systems can build learning assessments that test people on their usable knowledge from a document of content. Integrated platforms can coordinate all the activity so that GenAl learning systems naturally reflect changes in the technology and build on prerequisites that came before.

Moving at speed goes beyond the technology. There must be clear lines of communication and accountability, with direct input from the business leaders.

Relevance

A technology company had a partnership with Apple and decided to upskill their organization to gain more proficiency in selected mobile phone applications.

Unfortunately, these skills had little or no relation to the company's priorities. Six months after the training, more than half of the people who went through it said they never used the skills. Other than good relations with another company, there was no measurable return on the investment made.

Most companies cannot afford this type of project anymore, because of the opportunity cost. They need every bit of L&D resource to realize their business priorities - which depend on employees gaining real skills, instead of just credentials, and using them on the job. They need to gain relevance.

Being relevant can be as simple as checking in regularly with management, and being included in strategic sessions where the workforce skills are needed. It doesn't require a complex skills taxonomy, or a process for cascading training down through the organization. A CLO who listens to the organization and understands what it's trying to accomplish in the marketplace can volunteer suggestions: "Here are our greatest gaps. Here is where I can help create a talent supply for them. Here's what we need to get it done."

As you adjust your offerings, take a talent lifecycle view. Work in an agile, collaborative manner with talent and business leaders to identify the organization's long-term needs. Consider a wider range of skills and how to develop them: buy, build, or borrow?

Divide the function's work into three types of content:

• Table stakes: These are the traditional elements, such as compliance-based training or operational basics. Frame this as a stable set of core learning offerings which do not need continual reinvention. Deliver them at a lower cost, so you have time, money and attention left to develop your ability to surge. Some of this may become guidance for particular situations, implemented with GenAl, used at the moment people need them to conduct a maintenance operation or write a particular type of document.

• Fundamentals: These are the enduring human capabilities that matter. They set people up for success, and yet they have not necessarily been learned in business school - or any school. They include cognitive capabilities such as complex problem solving, creative thinking, and analytic logic, plus the skills of human-to-human communication and emotional intelligence: team management, mentoring and coaching, and conflict resolution. These offerings are tailored to reflect your organization's needs for higher-quality management and leadership. They may evolve as your organization develops.

• Surge: These are the critical skills needed for greatest business impact. Some of them are specific to particular technologies or practices: GenAl, robotics, biotech, or others. They are urgently needed now, but they may not have much longevity. Most skills learned 10 years ago are obsolete, and the half-life of a skill learned today could be as little as 5 years. Therefore, embrace adaptive design. Create programs that change rapidly, and that can be adapted to the specific skill levels of individuals and needs of the organization. Tailor learning pathways to people in specific functions like sales, customer service, user interface design, procurement, or R&D.

A skills accelerator invests most heavily in the surge and fundamentals, continually adapting them to a closer fit with the organization's priorities. This includes follow-up. When a company trains people to use a new robotics technology, it needs to change the staffing and evaluation systems accordingly, so they set people up to use these new skills back in the plant. Otherwise, they'll revert to their old ways. Viable follow-up methods include group discussions at the workplace, hourly pay incentives for using the new approach, and involving the individuals in suggesting adjustments to the system. It can also include certificates and badges to post on LinkedIn, but these tend to be appreciated most when people recognize the certification as relevant to their jobs or their own goals.

Scope

Any critical skill-building effort must clear the hurdle of scope: Reaching beyond a few business units to the whole of the organization. Broader scope requires changes in organizational infrastructure. The whole business -including HR, IT, operations, and governance - must be in sync with the skills accelerator.

Establish rules and investment so that L&D will be able to surge as needed, without delays in approval. Deploy changes in elements such as governance models, funding, incentives, role expectations, compensation, credentials, review criteria, and hiring criteria.

For example, your current compensation structures may set pay based on role and tenure. Change them to reflect employees' skill levels. Organizational rules may discourage individuals from practicing their new skills - either in their jobs or in their external lives. Revise them to encourage learning. The corporate culture may inhibit upskilling - so that when people return from a learning program, the manager ignores their new abilities. Educate managers and employees on the value of these new capabilities, ideally by showing them results. It may be cumbersome now to identify training and apply for new roles where the skills are needed. Install an internal digital platform for helping people do this.

The elements of a skills infrastructure are often designed separately from each other. Each has its own legacy - in L&D, HR, procurement, and IT. To build an organization's competence, they need to be integrated into a whole.

The leadership of one pharmaceutical company learned this the hard way. They agreed that the marketing group needed to be more data-driven and approved a learning program for proficiency with analytic tools. However, few marketers signed up. They simply didn't see the value in gaining these skills. Only when the performance management process changed to include data proficiency did the marketing organization pivot.

As you develop scope, continue to collect and analyze data about outcomes, including employee performance, roles, accomplishments, learning, and career paths. Use this data to help you continually revise and improve the offerings.

One professional services firm conducted knowledge assessments of its scaled-up L&D programs, expecting to find a great difference between its basic courses and its advanced learning on the same technical subjects. Instead, they found little difference in actual performance. The outcomes improved only when people began using the skills on the job. This insight changed the conversations -- from "We need more learning courses," to "We need to give our graduates more experience in the field."

Transforming the L&D Function

The skills accelerator concept represents a new operating model for L&D professionals. If they cannot adapt, they risk falling behind other organizations.

CLOs can get started with a series of local moves:

Look closely at the link between the business strategy and the necessary skills. Gain a deep understanding of how its work is conducted and how its tasks are changing. Consider how technology is impacting the organization and what skills will be required soon.

Place the employee at the center. Design with the learner's motivation, engagement, and career benefit in mind.

Identify critical performance gaps. Don't get stuck trying to define them all. Pick just one to focus on.

Define a plan for that first performance gap. Work with business leaders across the organization to create a roadmap for building the skill supply in that area.

Ensure foundational data elements are in place. Look for KPIs and other data related to performance, for use in demonstrating progress, sensing trends, and defining gaps in a manner meaningful to the business.

Bring the learning effort into the flow of work. Develop managers' coaching and teaching capabilities. Encourage first line leaders, for instance, to assign their staff to tasks that make use of the skills they've learned. Demonstrate the power of experimentation and reflection on the job. Train managers to ask their direct reports regularly: "What have you learned this week? How can you use it next week?" Subtle changes of that kind can rapidly raise upskilling impact.

Pay close attention to the results. Track the outcomes of this effort, and how they have affected revenues and capabilities. Create a narrative that demonstrates what

worked and redesign your efforts to learn from what didn't work.

As L&D professionals, our role is evolving. With approaches like the responsive skills accelerator, we foster a culture that supports and empowers L&D.

A responsive skills accelerator can revitalize a company. For example, when a telecommunications company made customer focus a key priority, the L&D function became a catalyst for change. It worked closely with business leaders, internal communications teams, and the talent acquisition function. Top management ensured that time was dedicated to learning. Other priorities were paused to focus on building skills. Leaders themselves participated, modeling the importance of the new capability for everyone. There were new KPIs and hiring criteria. The entire culture shifted.

This whole approach is also transformative for the individuals it engages - sometimes at a massive scale. A professional services firm in India sought to recruit staff for coding and other baseline technology work. There was not enough available talent in India with the requisite tech degrees, and the costs for hiring degreed people were prohibitive, so the firm's L&D function looked for another way to fill the gap. It offered an online test to find people who could be trained.

Thousands of people were selected based on their test results and assigned to one of 300 different upskilling paths. After an 8-week intensive program designed for each path, the graduates were given real-world assignments. They performed better at these jobs, on average, than college graduates with computer science degrees. In addition to dramatically improving the firm's margins, this program changed the lives of the recruits, who suddenly leapfrogged into a high-earning profession.

Changes like this are often regarded as rare: worthy of celebration because they happen so infrequently. With a skills accelerator in place, they happen all the time. This is simply how the L&D function operates. The business needs and value are a core part of its operating model. It routinely creates and implements strategic approaches for improving performance and overall effectiveness, and changes peoples' lives for the better. By investing in the skills accelerator approach, the L&D function can gain the pace, relevance, and scope that it has needed all along.

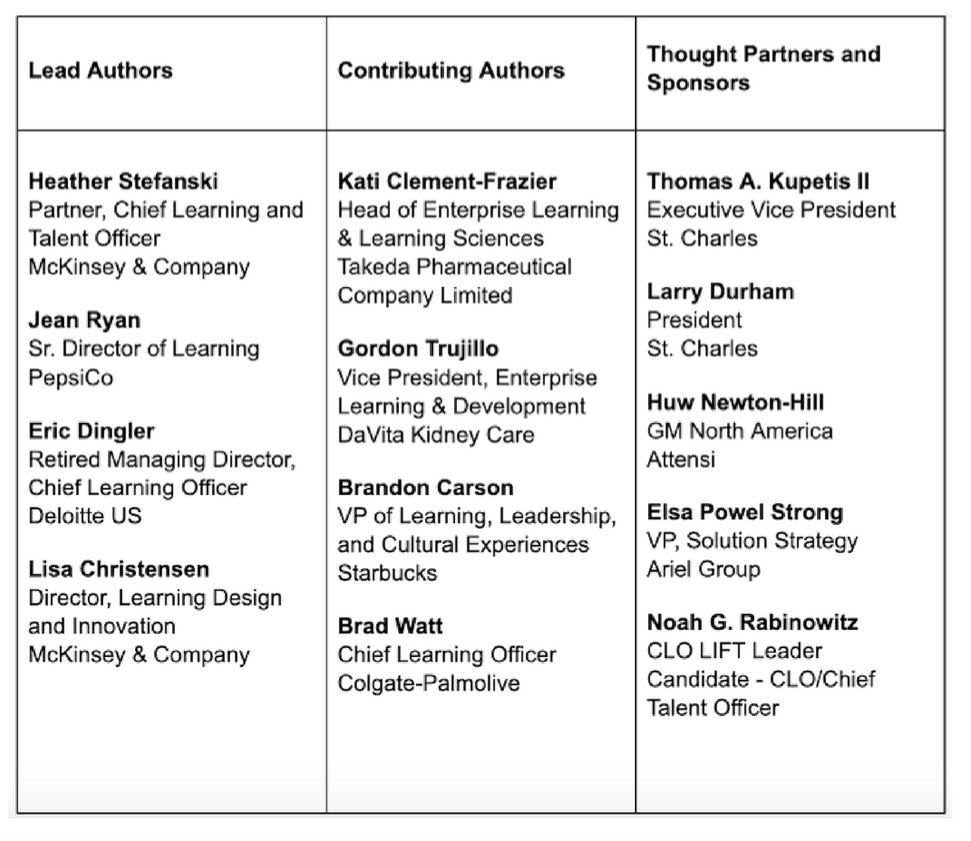

About the Authors

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all the authors and thought partners for their invaluable contributions to this article. Their combined expertise and insights have been instrumental in shaping the content, providing readers with a comprehensive understanding of the benefits of adopting a skills accelerator approach and transforming the L&D function to deliver real-world capabilities.

The Learning Forum + CLO LIFT Leaders

Brian Hackett, Founder and CEO of The Learning Forum

Meighan Hackett Poritz, Co-founder and Managing Director, The Learning Forum

Noah G. Rabinowitz, CLO LIFT Leader and Candidate for CLO/Chief Talent Officer